Some of you may have heard that there were originally 190 Pokémon planned for the original Japanese Red and Green versions, 39 of which (perhaps 40 – more on that later) were scrapped because of memory issues just before debugging began.

The primary evidence for that is found within the internal code of the games – more specifically, in the internal Pokémon ID list – where most of the details for each Pokémon are stored.

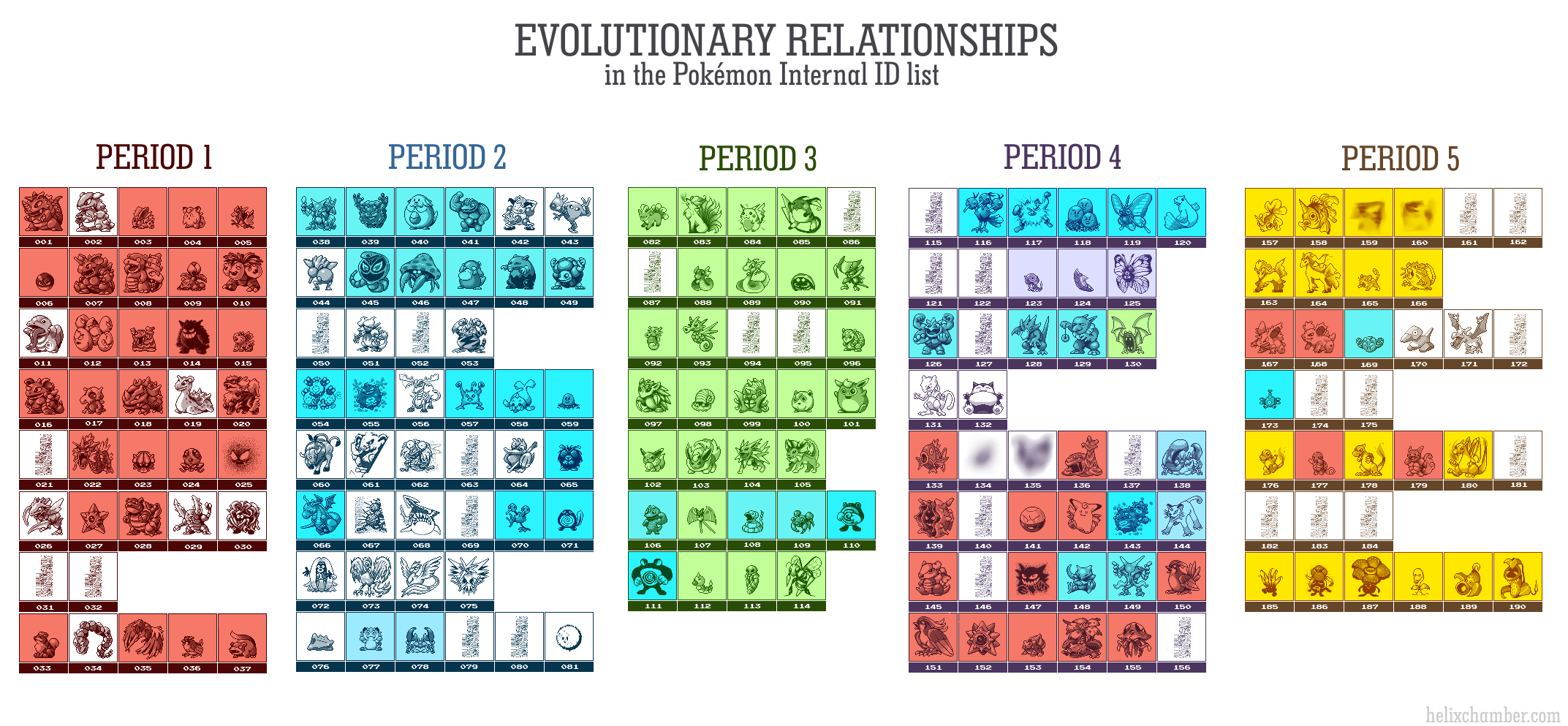

At first glance, this list may look completely random: it starts with Rhydon at 001 and ends with Victreebel at 190, the evolutionary lines are often fragmented, third stage evolutions are listed before their respective previous stages, the starters and the legendaries occupy random slots, and so on.

As messy as it may look, this list also evokes a feeling that something hides deeper within – as if the order of the Pokémon adheres to a sort of mysterious logic. Interviews with the developers seem to hint at the fact that the list follows the very order in which the monsters were coded into the game, teasing the curious with the promise of a glimpse into Game Freak’s creative process, and therefore, into the development history of the first ever Pokémon games.

We accepted the challenge and tried to make sense of the internal order to discover what kind of choices Game Freak made and the reasoning behind them. You’ll bear witness to a logic so concise that you may come away remembering the internal Pokémon order better than the final Pokédex order.

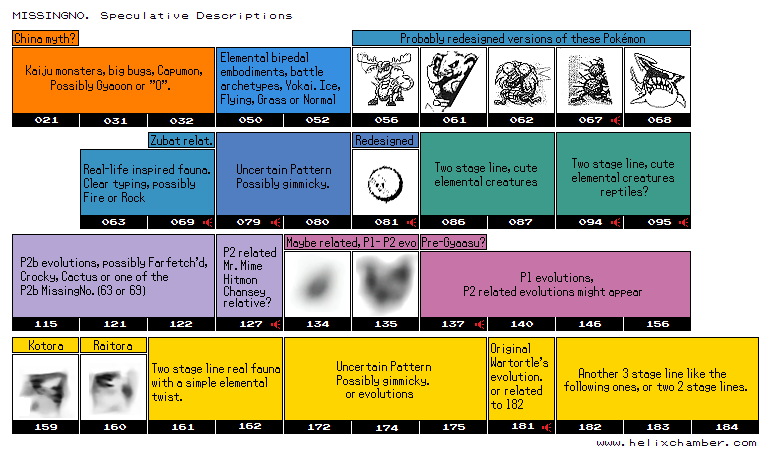

Using pattern recognition, first-hand sources, and vestiges in the game data, the primary objective of our research is to find hints as to the identities of the MissingNo. at the hypothetical last stage of development before their deletion – when all 190 spots of the index list were allegedly filled with usable data. Our secondary, broader objective is to learn about the thought process behind designing the monsters and the games themselves – to discover relations between different designs that aren’t obvious in the final release – to find traces of alterations in the game and monster designs throughout the roughly 5-year period of development.

WHAT IS A MISSINGNO.?

There are 190 slots intended for Pokémon in the code. Within the list of 190 are the 151 extant first generation Pokémon as well as 39 unused slots, which are comprised of almost identical data, all named “MissingNo.” (けつばん Ketsuban, lit. “missing number”) To clarify, the glitch “Pokémon” that begin at slot 191 and extend to 255 are different parts of the game code, like trainer classes, being read as Pokémon data, and are completely invalid.

Here are some quick MissingNo. traits from Glitch City Labs:

- Each MissingNo. is number 000 in the Pokédex, and is Bird/Normal-type. Bird-type is an unused type in Generation I.

- The algorithm for calculating MissingNo. data comes from its Pokédex number (000), so as a result of the calculations that the game makes, each MissingNo. uses the same invalid location for all of its data – Biker trainer data, to be specific. As this data is read as Pokémon stats instead of trainer lineups, the data translates in a strange way.

- 36 out of 39 MissingNo. have identical garbage sprite data. The other three use non-playable Pokémon sprites (Ghost, Kabutops skeleton, and Aerodactyl skeleton).

- Most of their cries are a generic Nidoran cry – these placeholder cries can also be heard in the Gold and Silver Spaceworld 1997 prototype for all of the new Pokémon’s cries. A handful of the MissingNo. actually have their own unique cries, leaving us with clues to their identities.

For a thorough analysis check out Crystal_ ‘s article.

In the 2000s, the nature of the MissingNo. came to light, and fans naturally wondered if there were, at one point, a total of 190 Pokémon. Morimoto himself confirmed this theory when responding to a fan; the team “cut the designs to save them for later” (just how later is surprising).

The various internal lists don’t always seem to be chronological; however, a slew of external evidence allows us to come to the conclusion that at least the Pokémon one is mostly chronological (since Rhydon has been confirmed to be the first ever designed Pokémon and there’s generally evidence that most of Pokémon from spots 1 to 37 were present right from the beginning).

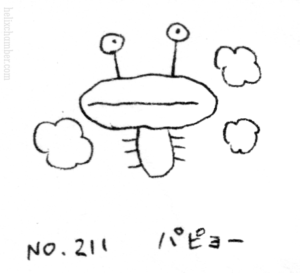

We know that at some point (probably late 1994 – mid 1995) an official list of monsters titled “PM (Pocket Monsters) Kaiju Zukan” (怪獣図鑑, Kaiju Illustrated Catalogue) was printed for reference. It sports a fairly fancy cover and logo, in addition to names and sprites of every Pokémon in their internal order. Its presentation may imply that it was supposed to be a document not just intended for the GF crew, but perhaps as a compendium for Nintendo, Creatures/APE, and other companies involved in the project at large and may have been the last official document featuring complete names and back/front sprite depictions of every MissingNo. in their near-to-final form, as they were supposed to appear in the games.

We know that at some point (probably late 1994 – mid 1995) an official list of monsters titled “PM (Pocket Monsters) Kaiju Zukan” (怪獣図鑑, Kaiju Illustrated Catalogue) was printed for reference. It sports a fairly fancy cover and logo, in addition to names and sprites of every Pokémon in their internal order. Its presentation may imply that it was supposed to be a document not just intended for the GF crew, but perhaps as a compendium for Nintendo, Creatures/APE, and other companies involved in the project at large and may have been the last official document featuring complete names and back/front sprite depictions of every MissingNo. in their near-to-final form, as they were supposed to appear in the games.

In other words, we might say our aim will be primarily to research the MissingNo. as they appeared in the Kaiju Dex, just months before they disappeared forever.

Have all the Missingno. even been coded into the game?

These traits seem to imply that the 39 slots taken up by MissingNo. were meant to be occupied, but the data had been overwritten or, in some cases, specific data was never there to begin with. As an example, we already know that the MissingNo. in slots 159 and 160 were Kotora and Raitora; they are some of the MissingNo. that do not have unique cries, meaning that they were either not given a cry before their erasure, or their cry data was deleted before the game was released.

It’s still unclear in what capacity the missing monsters had been programmed, the evidence is scarce and contradictory; some doubts might arise because most of data assigned to a Pokémon is connected to its Pokédex number, and very little data is connected with a Pokémon’s internal index number (read Crystal_‘s objections here and here to know more). Also the Tajiri Manga poll is seemingly missing some slots, and the Kaijudex seems to have some currently inexplainable inconsistencies in the sequence.

Are all scrapped Pokémon MissingNo.?

Both Sugimori and Tajiri stated that the crew had originally pitched about 250-300 Pokémon concepts, and that the plan for a long time was to code more than 200 monsters into the games.

Tajiri: We designed more than 200 Pokémon for the first games, then whittled them down to 150. This game [Pokémon 2] will exceed 200 Pokémon, but we already have over 350, which leaves me wondering which ones I should keep.

However not all of these Pokémon became MissingNo., this name refers only to the Pokémon that formed the roster of 190 monsters which were actually coded into the game, and then scrapped before debugging began. We’ll refer to the other circa 110 scrapped Pokémon as “Lost Pokémon” as trying to trace the original 300 pitches would be a desperate, Herculean task, but of course, we will also cover a bunch of unused and placeholder monsters that might fit more in the 300 count than the 190 bunch. For example, this analysis will also give us a better understanding about whether Gorochu was one of the MissingNo., or was scrapped before the 190 cut.

We’re fairly positive that the Tajiri Manga monsters have to be included in the MissingNo. list, albeit pertaining to a previous development phase (possibly 1993) but we must also acknowledge that their design and identity might’ve changed dramatically during the final years of development (especially the ones marked △ on the voting sheets).

For argument’s sake, we will consider a total of 40 missing monsters, also assuming that the Tajiri proto-mons remained pretty much the same (at least in concept) before debugging.

This claim can be substantiated just by looking at proto-Seel and proto-Weedle. Seel has always been a seal-like creature, and the Weedle line was always a three-stage bug line. As thus, Game Freak may have dramatically changed monsters’ designs, but they didn’t break their reference pattern on a regular basis.

According to Shigeki Morimoto, Mew was designed and added by him after the game was debugged as a kind of – quite risky – Easter egg for the crew. Our consensus is that Morimoto just placed his new Pokémon in the first empty MissingNo. slot available. Whether that was its original slot or Mew was actually meant to be in the game in an earlier stage, we don’t know for sure; however, Morimoto also stated that Mew was originally intended to only appear as a namedrop in the Pokémon Mansion Journals.

According to Shigeki Morimoto, Mew was designed and added by him after the game was debugged as a kind of – quite risky – Easter egg for the crew. Our consensus is that Morimoto just placed his new Pokémon in the first empty MissingNo. slot available. Whether that was its original slot or Mew was actually meant to be in the game in an earlier stage, we don’t know for sure; however, Morimoto also stated that Mew was originally intended to only appear as a namedrop in the Pokémon Mansion Journals.

Morimoto: We put Mew in right at the very end. The cartridge was really full and there wasn’t room for much more on there. Then the debug features which weren’t going to be included in the final version of the game were removed, creating a miniscule 300 bytes of free space. So we thought that we could slot Mew in there. What we did would be unthinkable nowadays!

We must also briefly acknowledge the case of the suspicious “Mew” trademark, filed during Capsule Monster‘s development on May 9, 1990 (Registration number 2636685-12, Registration date 1994/03/31). Its spelling was, however, a bit different, being ミュー and not ミュウ. Was it the very same Mew? The answer is actually no – the patent was originally submitted by Yokohama Rubber Company for their “μ” (Greek mu) line of DURAN tires. In 1999, however, Nintendo, Creatures, and Game Freak applied to nab the trademark and change it to ミュウ, which is how their names got on the document. To conclude, Mew was probably not conceived as early as 1990.

Strong evidence of Mew’s later inclusion might also come from the fact that Mew’s sprite is actually stored elsewhere in the ROM banks (Bank 01, unlike the rest of Pokémon whose sprites are stored in banks 09 to 0D) and its unusual cry ID values, at least for a Pokémon placed that early.

From now on we will assume that the spot in the index list that Mew occupies in the final release was originally home to another Pokémon, thus raising the number of Missingno. we’re researching to 40. We will delve into this topic further in the next article.

OUR METHOD

A Period is defined by a big change in the Pokémon design concept, both inherent to the list and testified by the sources. It doesn’t mean that Pokémon in the same period were all programmed in one session, but that they were designed and coded at a similar time, having in mind a specific direction for the game.

Reading through the internal list, with some additional proof from interviews and sources, the Pokémon Internal ID list can be broken down into five primary groups of monsters:

- PERIOD 1: The original Capumon. Kaiju-inspired dinosaurian monsters, childhood idols, RPG inspirations and tropes.

- PERIOD 2: Emphasis on types, Morimoto and Fujiwara join the team. Elemental Pokémon and Pokémon inspired by real-life animals are added to test the battle system and create a more diverse ecosystem.

- PERIOD 3: Nishida joins the crew, cute Pokémon are added; the concept of evolution is vastly expanded with entire 2- and 3-stage lines added, as well as stone evolutions, split evolution, and more elemental Pokémon.

- PERIOD 4: Evolutionary relatives of Pokémon added in previous periods.

- PERIOD 5: The most eclectic group with more common 2-stage lines, stone evolutions, an odd bunch of Pokémon, and finally, the starters!

We’re going to split periods into further categories that we call patterns, denoted by a letter following the period’s number, for example: Period 3a, or P3a for short. This is important to break up those relatively big groups of Pokémon into smaller batches that share common design features and philosophies.

The evidence follows this theory fairly well; Pokémon like Gyaoon, Cactus and the “feline/squirrels” Kotora and Raitora were easily “predictable” in the framework provided. Let’s just take Cactus as an example.

|

According to our definition, Cactus is a Period 2b MissingNo. These Pokémon are all real-life inspired creatures with a clear typing, and P2b also has a suspicious lack of grass Pokémon. A grass real-life inspired Pokémon would be expected among P2b MissingNo., as they seem to have an example of every possible type. And what’s even more surprising is that if we were to theorize that the Grass one was actually the owner of the leftover cry in slot 067, we could’ve also speculated that it had thorns, because that cry and its variations are associated with spiky monsters! |

Of course, some monsters pop up in the list as oddities, but unless the missing ones are ALL exceptions to the patterns, we’re pretty positive this research will clear up our understanding of who went missing, giving you a solid framework to place your guesses and speculations. Of course, we’re also going to express our hypotheses in the last article of this series, but we’re mostly going to present you with the most logical identification, well-aware that pattern breaking is not uncommon in the creative process.

We suggest you to be patient and don’t jump straight to the last part, reading the whole research will equip you with the correct context to understand the identifications. Obviously, many questions pertaining to the identity of the 40 MissingNo. will remain mostly unanswered, but pattern recognition is perhaps all that we can hypothesize about with substantial basis in reality.

Furthermore, we’ll have an insightful reconstruction of the development of the first Pokémon games, and, comparing the Pokémon list with the other internal lists and with external sources, we could also begin to imagine how the Gen 1 proto-Pokémon builds might’ve looked like.

| ⇐ | INTRO | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | ⇒ |

| MISSINGNO. OVERVIEW | LOST POKEMON OVERVIEW | ||||||

knowing how some missingnoś get reused in later games (like how jaggu later became sharpedo in gen.3) i have done a little research myself and have recently discovered that in the debug menu (which is only in german for some reason) there are some remixes from song form gold and silver and crystal. i think this means that gamefreak and nintendo were either testing the gba’s limits or were going to make a jhoto remake on the gba instead of the ds.