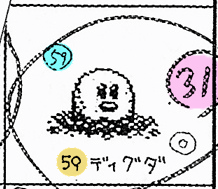

Anyone who has seen the sprite sheet in the recently published Satoshi Tajiri manga may have tried to make sense of those strange numbers that each Pokémon was given. Some have numbers preceding their names, some have pencil-written bold numbers, others have thin numbers in circles in the upper left corner of their panel. Some Pokémon have one number, some have two, Diglett has three. What is that all about?

First let’s get one thing out of the way. Diglett is mar ked with a 31 because it placed 31st in the internal popularity contest that this sprite sheet was used for. It’s also marked with two 59. If you check the internal index list then you see that, indeed, Diglett is in slot 059. So these are index numbers, right?

ked with a 31 because it placed 31st in the internal popularity contest that this sprite sheet was used for. It’s also marked with two 59. If you check the internal index list then you see that, indeed, Diglett is in slot 059. So these are index numbers, right?

Well, only one of them actually seems to refer to the index number. See, on the top-right panel of the same sprite sheet, we can see Pokémon that are marked with only one number – the circled one – and they don’t at all correspond to their internal index numbers.

So what exactly are they?

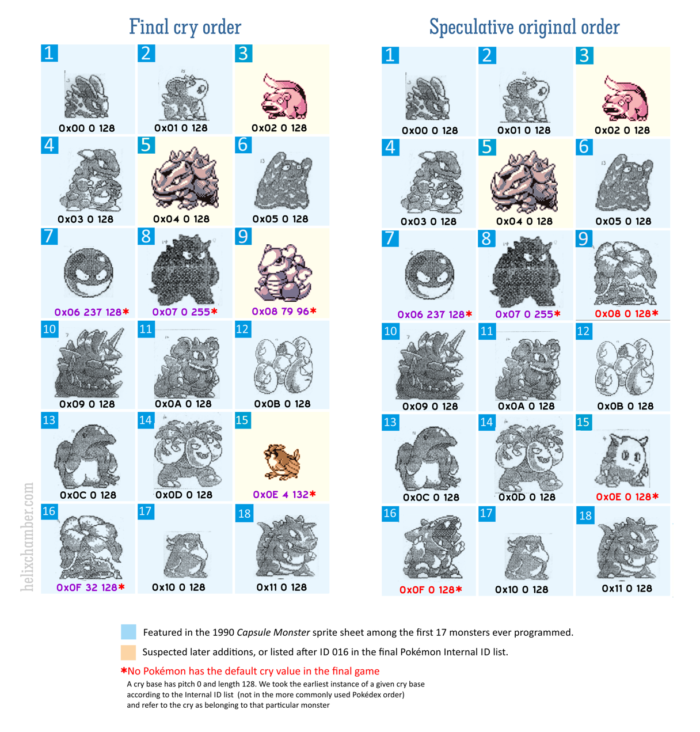

At least for the Pokémon in the panel on the right, these circled numbers refer to the cry data of each Pokémon. Specifically their base cry.

Each Pokémon’s cry is made of three parameters: the base (or simply, the melody); the pitch; and the length. There are only 38 base cries, so for all 151 Pokémon to sound different, they took a much smaller set of base cries and modified their pitch and length to create a unique sound that each Pokémon makes; these cries are used when a Pokémon is encountered, sent out to battle, or other situations like viewing it in the Pokédex. You can easily come to understand how this works; for example, here are the parameters for base cry 0x0D (the fourteenth in the list), one of the most recognizable cries in the game:

| Index ID | Name | Base | Pitch | Length | Play |

| 10 | Exeggutor | 0x0D | 0 | 128 | |

| 48 | Drowzee | 0x0D | 136 | 32 | |

| 72 | Jynx | 0x0D | 255 | 255 | |

| 129 | Hypno | 0x0D | 238 | 64 |

The first Pokémon following the Internal ID order (not the Pokédex order as generally assumed) that has a given cry base most commonly has the pitch and length parameters of its cry set at 0 and 128 respectively, which makes us believe that these were, in fact, the default values for these parameters.

This shows us which Pokémon may have been the original user of a given base cry, and how the default parameters were altered for other Pokémon that reused that base. If no Pokémon uses the default values of pitch and length parameters, or, a Pokémon that does use the default values appears later in the index list, then it’s safe to assume that the original user was the one that appears first in the internal ID list, no matter what the other parameters are.

The subject of cries is more interesting than you might think, and warrants a completely different article devoted to how they are programmed and matched with certain Pokémon.

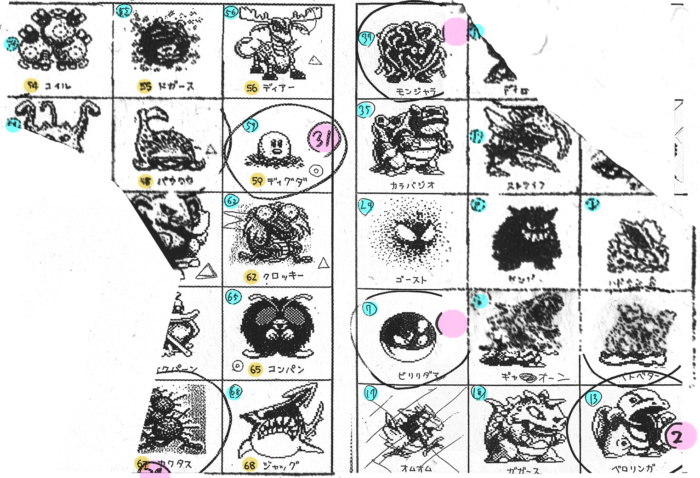

Moving back to the Satoshi Tajiri manga charts, we can see that Gastly is marked as 29, Voltorb as 7; Lickitung, Spearow, and Rhydon are marked with 13, 17, and 18, respectively. These monsters are displayed seemingly without a full sequence in mind. Our hi-res scans also show a blurred 8 for Gengar and 1 for Nidoran-male.

Tying this back into the cry data, what are the decimal value IDs of the cries used by these Pokémon? Nidoran has a base cry of 0, Voltorb – 6, Gengar – 7, Lickitung, Spearow, Rhydon – 12, 16, 17. Gastly’s cry occupies spot number 28.

As you can see, for whatever reason, numbers that directly correspond to the base cry IDs (plus one, to account for hexadecimal counting starting at 0, not 1) were written down on a Pokémon voting sheet. What does this mean? Was this simply a programming note, or maybe the order of base cries was intended as an early attempt to create a coherent order of Pokémon, kind of like a prototype Pokédex order? Regardless of speculation, at some point, in some way, the cry order was definitely important enough to the developers to warrant its appearance on the voting sheet.

THE GAMEINFORMER DOCUMENTS

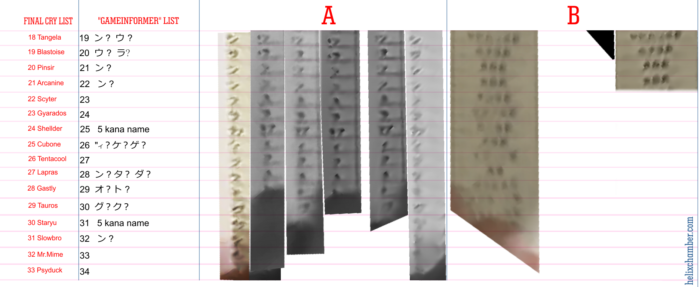

In the video interview that GameInformer conducted with Game Freak in May 2017, Junichi Masuda browses through some development documents, picking out a few to discuss their significance.

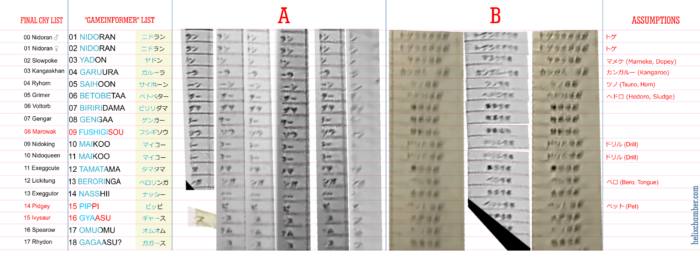

Given the meticulous nature of Helix Chamber, we revisited this interview over a year after it was published in order to take a closer look. Attempts at finding something substantial to our research within the pages that Masuda perused (amid an Apricorn chart for Generation II and a photocopy of an article with a Dragon Quest screenshot) resulted in the discovery of a list of around 38 Pokémon in their cry order – both of the Nidoran first, then Slowpoke, Kangaskhan, and so on.

The title of the document begins with “PM全xx”, which basically means “Pocket Monsters All (unreadable kana)”. The content of the page consists of three columns.

The title of the document begins with “PM全xx”, which basically means “Pocket Monsters All (unreadable kana)”. The content of the page consists of three columns.

Unfortunately, the only text we can read with relative ease is that of column A, which contains Japanese Pokémon names. Column B, however, seems to be the species name – which is the category that you see in the Pokédex, like Grimer and Muk’s ヘドロ hedoro; in English, the “Sludge Pokémon.” Each entry in Column B apparently ends with the same two kana, similar to how the final’s species title is structured with “Pokémon” at the end, but they are too blurry to make out properly. Column C, which is longer, seems to look like short descriptions or other names, but we’re pretty much unable to read it. In case you’re well acquainted with Japanese writing, have 20/20 vision and want to help, we’re providing our best resolution screenshots and enhancements in the media section below.

Although we can only see the final two or three kanas of each name listed at most, we can definitely discern what most of them are. Just like the mysterious numbers in the chart from Satoshi Tajiri manga, the list corresponds to the final cry order for the most part, especially rows 01-18 (cry IDs 00-17). There are a couple of notable differences, though.

For one, フシギソウ “Fushigisou” (Ivysaur – probably still resembling Venusaur like its Capumon sprite) seems to be listed ninth on the list, corresponding to cry number 0x08 instead of the one that it uses in the final game, 0x0F.

For one, フシギソウ “Fushigisou” (Ivysaur – probably still resembling Venusaur like its Capumon sprite) seems to be listed ninth on the list, corresponding to cry number 0x08 instead of the one that it uses in the final game, 0x0F.

When discussing the Tajiri Manga voting sheet earlier, we deliberately didn’t mention Blastoise and Tangela (and also Pinsir, whose number starts with a 3 and they generally seem to be grouped both in the final and the proto lists), even though they’re clearly visible. This is because they represent a puzzling exception that warrants its own discussion.

After Rhydon at spot 18, the same as the cutoff in the manga panel, the list becomes unrecognizable as the motion blur begins to warp every kana into what looks like a sequence of -ス (-su) and -ン (-n). We can’t even guess which Pokémon these slots used to host, however, comparing the list with the cry order, it’s clear enough that カラバジオ (“Caravaggio”, Blastoise) and モンジャラ (“Monjara”, Tangela) are not in their expected slots.

As mentioned, those two, and probably Pinsir (we don’t know the last kana of its proto name) have base cries in the 18-20 range, so you would expect to find them in slots 19-21 (Cry ID numbers plus one), right after Rhydon in the GameInformer list. Yet, supposing that they had the same names as the manga poll, they seem to be absent.

This trio seems to be incorrectly numbered both with their current Internal ID and their cry IDs. Only Gastly’s last kana, ト (the ト in ゴースト “Gosuto”, which was its prototype name) might be somewhat discernible and placed in accordance with both the cry order and the sprite sheet.

This points us towards two possibilities:

- Their cries at some point in development actually did have decimal values of 34-36 (one less than written, due to hex notation) and were later changed, or…

- The numbers in circles (past some point anyway) were actually the same as the index order. This is definitely the case in other panels, where numbers in circles ARE the same as index numbers of each Pokémon.

The second option opens a completely new possibility, being that the internal index order might have been completely different at some point and instead was identical to the order seen in the aforementioned GameInformer list, starting on Nidoran instead of Rhydon, and then continuing as the normal index order starting at 038 (either Kadabra or Graveler), jumbling the index order of the first 37 Pokémon (but, curiously, roughly preserving the first 18 in a relatively rigid group).

In such a hypothetical early variant of the index list, the Blastoise, Tangela, Pinsir group – now occupying slots 028 to 030 – would be placed on numbers 035 to 037, which in the final game are the slots where we can find Fearow, Pidgey and Slowpoke.

There exists a counterargument in the fact that the same manga revealed very early sprites, probably dating back to 1990 and the first Capumon pitch, showing the first 16 Pokémon from the actual index list, marked with their final index number, with the exception of only Rhydon who apparently was at spot 0, and the previously unknown one, possibly proto-Gyaaon (Gyaasu?), that was actually at 1.

There is a possibility that they tested an in-game Pokédex-like order at some point or even re-coded the first 37 Pokémon in a different order for whatever reason during the development and later reverted back to the previous version, but unfortunately, we can’t really know this for sure.

If the Blastoise-Tangela block really had been moved back seven slots upon reverting to the older index numbering, then it could mean that a bunch of early Capumon might . have been moved, or worse, deleted for good. These hypothetical Pokémon may not even hide behind a MissingNo., whose identities we strive so hard to uncover, surviving only in a bunch of speculative missing default base cries and those few warped kanas in the GameInformer frames.

- Download here the full list enhancements (16 Mb) with our guesses and tools to help with the reconstruction. Some knowledge of Japanese might be needed.

- Thorough Cry list with index order

- GameInformer Pokémon dossier

Doesn’t the name “Yadon” still belong to Slowbro at this point in time like in the 1990 pitch document?

we don’t actually know, because this list is marked PM and we have confirmation for Yadon to be Slobro only in Capumon:o

we don’t actually know, because this list is marked PM (Pocket Monsters) and we have confirmation for Yadon to be Slobro only in Capumon:o

Discovered this site after hearing about your recent romhack.

Had a look at Column C notes in the reconstruction images, as someone with some familiarity with the language:

Nidoran M and F: the ends of the lines seem to be 「てください。」, ‘Please [do smth]’, a request to the reader.

For Nidoran Male this makes ツノを[??]してください。, ‘Please make the horn[s] [??].’

Yadon: the end of the line looks like it could be 「するといい。」, ‘[doing smth] would be good’, though the proceeding な leaves me unsure.

I should mention that the dopey species is マヌケmanuke, not マメケmameke, but I assume the author of this article just wasn’t familiar with Japanese.

Saidon/Gyaoon: the start of the line seems to be 「口を少し」, ‘[smth] the mouth a bit’, seeing that sweeping stroke at the bottom of the third letter.

Garura: I see what looks like 「[1]やるよう[2?]してください。」 at the end of the first sentence, where the 1 looks like a を and the 2 may be に or で.

This makes a sentence structure of ‘Please [do x], like doing [smth]’

Biriridama: While I couldn’t figure out the mystery character, that pattern 「[AA]ーン」 is reminiscent of a sound effect, an onomatopoeia, especially with being alone in brackets.

ドドーン is a sound of an explosion’s ‘boom’, which could fit, though the images don’t look entirely like ドド.

「[??]ーン」 is also similar to some Pokémon names, however.

Fushigisou: Surprisingly for this far down, this one is the most readable.

「もっとスマートな[?]にしてください。」, ‘Please [make/give] it a [smart]er [?].’ The final missing letter would be a kanji, likely lost without better images however…

I leave [smart] in brackets here because スマート[smart] has taken on extra connotations in Japan, with a common meaning of slender/slim/fashionable/stylish.

Since these generally all refer to someone’s appearance, it’s possible the missing letter is 絵, ‘image’, making something like ‘Please give it a [slimmer/more stylish] image.’

Beyond that unfortunately, the distortions are more severe and I couldn’t work out anything more.

And despite all these fragments, it’s still hard to tell what these notes are referring to.

‘Nidoran’s horn/s should be [smth], Fushigisou’s [smth] should be better-looking’ seem to suggest it’s notes or comments on draft images.

The page’s title is also still a mystery.

Either way, it was interesting to try and decipher, at least.

aw gosh! thanks! I’ll forward this to the team 😀 I’m answering properly later

Here’s an observation I made that might help here, as well as a theory:

On the second page of the Capumon sprites (the one with Omega), there are two numbers next to each sprites; the smaller one corresponds with the Index number of each Pokemon, but there’s also a larger one next to each name. After more inspection, I determined that they correspond to the final game’s cry list, with most of them lining up with the list after Rhydon’s cry; specifically, they appear to be their final cry decimal placement plus one. For example, Tangela has the number 19 next to it’s name, and its cry in the final is base decimal 18, Pinsir has 21 next to its name and its cry is base decimal 20. As further proof, Rhyhorn has the number 5 next to its name and its cry is base decimal 4 (the only one that’s before Rhydon’s, incidentally).

However, two don’t match up; Omega has the number 20 next to it, and 20 – 1 is 19… which is Blastoise’s cry. Blastoise, on the other hand, has 30 next to its name, and 30 – 1 is 29, which is used for, among other things, the Squirtle line, which in ends up evolving from in the final release… but doesn’t share a cry base with.

My theory is thus: Omega was indeed originally the Pokemon that has Blastoise’s cry, and Blastoise originally had the base decimal 29 cry. Whether the latter played a role in Blastoise becoming Squirtle’s final evo or is a coincidence in that regard is up in the air, al least for me.

…aaaand turns you guys figured that out yourselves. At least I was able to come up with it independently, I guess?

Yea! XD we spent a lot of time on the cry analysis, perhaps the site is a bit of a maze at the moment and some info are also scattered on our Twitter. Anyways, good intuition 😀 i’ve seen you’ve posted a lot of compelling theories on our articles, i really wish we had something more to nibble on plot-wise 😮

ahah yea, Blastoise originally having Kamex’ base cry is quite ironic xD But this could point in the direction that Omega was scrapped for good in the late 92/early 93 poll. In that case slot 21 could’ve stayed vacant till Mew or hosted another lost mon ò_o fascinating!